|

N AVAL AVIATION NEWS |

|||||

|

Published in the June 1976 Issue of Naval Aviation News |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

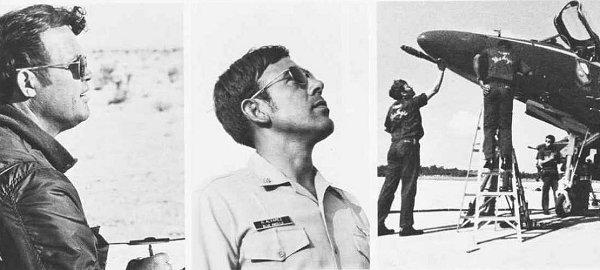

Above, left to right, maintenance officer and professional air-show watcher, Lt. Mike Deeter; top enlsited man, CPO Hector Alvarez; and crew working on a Skyhawk. Senior Chief Hector Alvarez, the Blue Angels' top enlisted man and maintenance chief, describes his crew as "self-starters." They have to be. The massive pressures inherent in meeting air-show requirements demand self-generated and total commitment. They must get the A-4s up and ready, on time, without fail, always. True, the squadron's Skyhawks don't require certain elements of support found in the fleet such as weapons handling or grooming of elaborate fire control systems. If a carrier-based aircraft goes down, every effort is made to get it up. But if that effort fails, the squadron loses a sortie. So be it. They'll make up the loss, hopefully, on the next go. The Blue Angels can't lose one sortie. And they don't. The 70-strong maintenance force won't let that happen. On those rare occasions when a radio conks out before a Blue Angel takeoff, or one of the planes suffers a flat tire taxing out or back in, a trouble-shooting contingent responds. Says PRC Ronn Penn, Alvarez's assistant, "We can change a tire in five minutes, a radio in ten. Once we replaced a starter unit in 12." Usually, the crowd will never notice. Adds Penn, "Here at El Centro we get our act together. Once we go on the road we keep it together." Even during training, the troops wear their air-show uniforms - blue trousers, short-sleeved blue shirts and polished safety shoes. Some members are more visible, as far as the audience is concerned, than the "hanger" force. A crew chief and two others are married to each A-4F. They are part of the formal activity at the shows - the walk-down, start, taxi-out, return, and shut-down portion of a flight. Behind-the-scenes labor, especially in the training phase and between weekend shows at the Pensacola home base, is obviously as important. The planes are waxed weekly, spot-painted almost daily. Adds Chief Alvarez, "We pay special attention to control rigging and scrutinize the airframes thoroughly after every hop. Since each pilot flies the same gird, he is literally 'form-fitted' to it. That plane's crew is able to note and correct, as necessary, any deviation from the norm the pilot is used to." Blue Angel Skyhawks are about eight or nine years old and have seen heavy fleet duty. They differ, only slightly from standard versions. The accelerometer gauge is oversized, a spout on the underside emits 10-10 oil for smoke trails, and highly polished aluminum edges on the intakes and leading edges are for cosmetic purposes. The squadron inventory includes Fat Albert, the Hercules support plane which is manned by a Marine crew and serves as a first-class airborne AIMD shop as well as transport. Number Seven is a TA-4 flown by narrator, Lt. Nile Kraft. A pair of spare "show-birds" are on hand at Pensacola. For some, the Blue Angel experience yields rewards other than the deep-seated satisfaction after a particularly good demonstration. "Where else could an AK get flight time in a jet, close to 100 hours a year, no less," declares AK1 Bill Simms. He and AME2 Pete Thornton are crew chiefs for the two-seat Skyhawk, and alternate traveling with Lt. Nile Kraft, the monitor, to show sites. They ensure that support requirements are satisfied before the balance of the team arrives. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

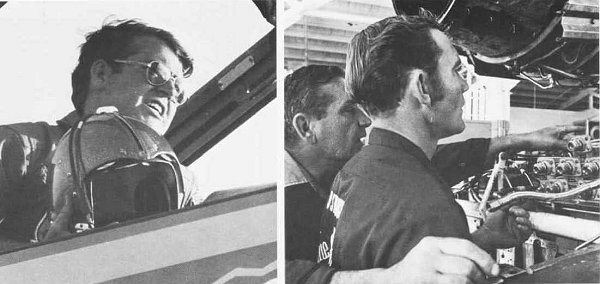

AME2 Pete Thorton settles into TA-4's rear cockpit for a hop to air-show site. |

Dale Specht (McDonnell Douglas Tech Reps.) lends a hand to AMH2 Cliff Schuyvers. |

||||

|

Lt. Mike Deeter heads the maintenance department and is in his third Blue Angel year. The pressures don't seem to bother him, probably because he knows that his weighty responsibilities are mutually and aggressively shared by a volunteer force of self-starters. In fact, Deeter has time for the satellite chore assigned him by Skipper Jones. Although a 1520 designated officer and a non-aviator, he has become a professional air-show watcher. Says the C.O., "Mike has an acute sense of observation. He watches all our practice flights in addition to demonstrations before an audience, takes notes and briefs us where we make mistakes." Even skilled aviators couldn't detect the miniscule flaws the Mike Deeter records. He, Alvarez and other senior members of the team help handpick the troops. BuPers is not inundated with volunteers for the squadron. So, a concerted effort is made to find the best talent available and encourage people to join up. "We use our fleet or training command contacts to solicit personnel," explains Deeter. "Then we interview candidates at the many bases where we're scheduled to appear. Once accepted, a man works a probationary one-month period before being permanently assigned." Blue Angels' advancement prospects are the same as their fleet counterparts. But they receive a lot of cross-training in other ratings not usually available in all units. Yeomen can run huffers, AKs will change tires, and the AZs know how to paint airplanes. This experience yields career dividends. In recent years, enlisted personnel have been integrated into recruiting and public affairs duties. They may accompany the pilots on visits to orphanages, schools, hospitals and civic gatherings. They help sell the Navy to young men and women across the country. For road trips, usually 21 men travel on Fat Albert and support a show. The remainder work at Pensacola. Alternating the duty allows the troops to spend more time with their families. Importantly, there is an extraordinarily good rapport between the officers and enlisted men. Chief Penn explains, "I have never worked with better officers. There are no swelled heads among them and no doubt the other troops agree." Alvarez asserts, "Our pilots and crew take more pride in their aircraft here than anyplace else in the Navy. We have to. And I don't mean that just because we do things like removing our shoes before climbing onto a wing." Lt. Deeter amplifies. "Our purpose is singular: we must set a standard of excellence, not only for the civilians who watch us but for our own Navy personnel as well." A civilian who is part of the excellence, however, is Dale Specht. He is the Blue Angel technical representative assigned to the squadron by the McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Corporation. In his second year with the team, Dale has had plenty of carrier duty as a rep aboard the Forrestal and Independence. He's had 20 plus years maintaining airplanes and knows the Skyhawk like the back of his hand. He not only lends technical expertise, he's been known to get the back and front of his hands dirty helping crewmen on repair actions. What credentials must the Blue Angel have? The administrators, Lt. Leo Boor, who handles personnel matters, and CWO-2 Al Pully, the supply officer, have self-evident backgrounds, as do their enlisted staff aides. Captains Steve Petit and Steve Murrary fly Fat Albert with an experienced all-Marine crew. The maintenance specialists are an elite collection of professionals. Says Alvarez, "Motivation is vital. You have got to want to be a Blue. One of our men, for example, lost 75 pounds in three months to meet our appearance requirements. That's motivation." "Also," he goes on' "we look for 3.8 to 4.0 sailors. Experience level is not critical." One Blue Angel pilot voiced vivid testimony to the maintenance skills in the squadron. "I never worry about the mechanical condition of my aircraft. I must concentrate totally on flying and I can do this because I have absolute trust and confidence in our maintenance force. I know that plane is up and ready when it's supposed to be." |

|||||